Let’s talk about verbs.

In real life, a “verb” is something someone does. I run. You think. We build.

In games, “verbs” are very similar, but with one notable caveat. Because games are, obviously, not real life, the only verbs that you can use in a game are the ones that the game gives you.

For example, in Minecraft, I can “craft,” “shoot,” “hit,” “build,” or “mine.” I can’t, however, “talk.” No matter how hard I try to convince a skeleton not to shoot me or a villager to lower their prices, I just can’t do it.

Imagine if, however, you were playing Minecraft and happily building a fortress, and then someone came along and started convincing all of the skeletons to join their private army. You, naturally, would likely feel fairly frustrated by this. Even if you had no desire to build a personal undead legion, you would likely feel irritated by the fact that this new person could access a part of the game that was effectively off-limits to you.

Now, if Minecraft had a “Talker” class and a “Miner” class, and the Talker could talk, but not mine, and the Miner could mine, but not talk, then this wouldn’t be a huge problem. Both classes would have to work together to get anything done, and both would feel valuable. This is a fundamental part of specialization—the decision to sacrifice one “verb” in exchange for another.

Dungeons & Dragons, unlike Minecraft, has lots of different classes that can do different things. However, it has a huge problem, because its equivalents of Talkers can talk and mine, and its equivalents of Miners can only mine.

I’m talking, of course, about spellcasters and non-spellcasters.

Talking Is Not a Free Action

Let’s assume you’re a fighter and you want to climb a tree.

You can attempt to climb this tree by making a Strength (Athletics) check. However, so can the weak, sickly wizard who failed gym class. Now, you might be more likely to climb the tree than the wizard, but the wizard still has a right to try, and will actually succeed a reasonable percent of the time.

By contrast, the wizard can fly. No matter how hard you try, and no matter how lucky you get, you can’t do the same.

Here, wizards have more verbs than fighters. Both wizards and fighters have the verb “climb” (let’s call this a “shared verb”), but only wizards have the verb “fly,” and fighters don’t have any verbs to make up for it. The wizard has specialized into flight without sacrificing anything. The fighter hasn’t specialized at all.

If you’re looking to make a game where every player has an equal opportunity to contribute, this is a Bad Thing. This is further exacerbated by the fact that a lot of the shared verbs that non-caster classes excel at (climbing things, balancing on things, jumping on things) are either relatively unlikely to come up in meaningful gameplay (when was the last time you needed to climb a tree?) or obviated entirely by certain caster spells (such as spider climb, jump, or misty step).

Now, this wouldn’t be a problem if every group stuck to a standard adventuring day in which casters had to save almost all of their spell slots for combat. In this system, once you leave the battlefield, casters and non-casters are on equal footing. However, not only is the standard adventuring day a fundamentally flawed concept for the kind of “narrative sandbox” experience that most modern players want to have, it also fails to cover what happens on downtime or transitory days when the players don’t face any combat.

Few campaigns, after all, have enough combat encounters to exhaust caster resources on every single in-game day. If the party is trying to break into the Royal Bank, and the wizard knows dimension door and feels fairly confident that there won’t be many monsters inside, there’s nothing stopping them from blowing all of their spell slots on teleportation while the fighter patiently waits to be useful.

We can collapse verbs like “control,” “fly,” “teleport,” and “conjure” into a single category called spell verbs. These are verbs describing actions that are physically impossible in reality, but readily accessible with magic.

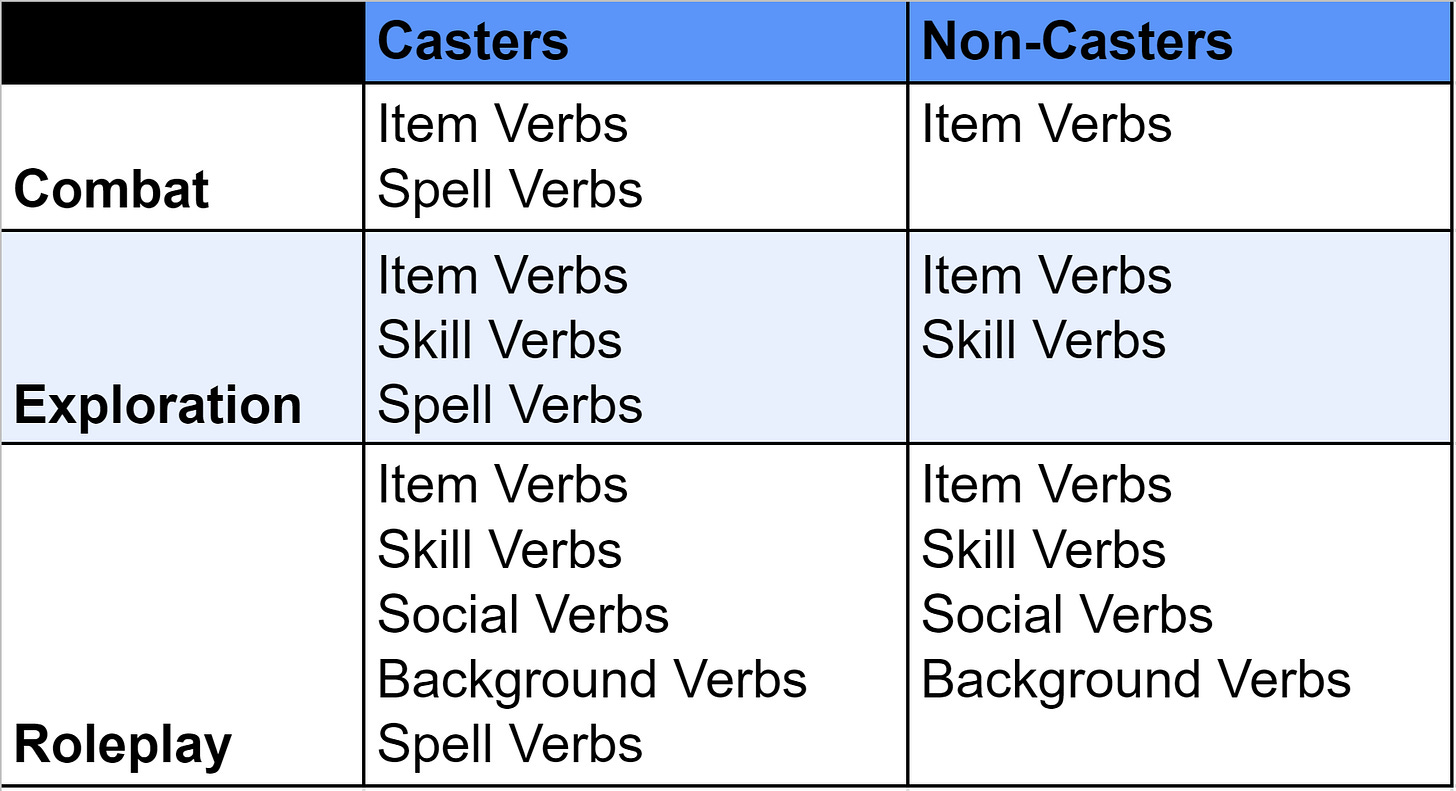

Dungeons & Dragons actually has a wide variety of verbs, which you can generally collapse into a few different categories:

Spell Verbs, which I explained above.

Background Verbs, which reflect the unique features that a character has from their chosen background (e.g., “find lodging” or “make a friend”).

Skill Verbs, which reflect a character’s skills and proficiencies (e.g., “recall information” or “persuade someone”).

Item Verbs, which reflect a character’s ability to use tools and resources (including both mundane and magical items).

Social Verbs, which reflect a character’s ability to communicate with others (e.g., “make an argument” or “invoke your reputation”).

Each of these verb categories is usually tailored to one of Dungeons & Dragons’ three main gameplay “pillars”: combat, roleplay, and exploration. For example, Background Verbs are usually optimized for roleplay, while Skill Verbs are usually optimized for either exploration or roleplay. Some categories, like Spell Verbs and Item Verbs, are exceptionally flexible and can be used in a number of different circumstances depending on the specific spell and/or item.

Here’s a table that reflects how these verb categories are divided between casters and non-casters:

There’s a pretty obvious discrepancy here! The casters can use all of the verbs that the non-casters can,1 but they can also use Spell Verbs.

Now, in combat, we somewhat2 make up for this fact by giving non-casters a relative boost: because they have more item proficiencies, their weapon- and armor-related Item Verbs are generally more effective than the casters’.3

This makes sense! Non-casters are, in general, people who use weapons and armor instead of magic. It’s completely reasonable that they’d get more mileage out of it.

But weapons and armor aren’t particularly useful in exploration or roleplay, which means that non-casters can’t lean on Item Verbs to compensate for casters’ Spell Verbs. However, exploration and roleplay introduce a new kind of verb: Skill Verbs.

Skill Verbs, though, are fairly infrequent in exploration. Athletics and Acrobatics checks, for example, tend to appear only rarely. Spell Verbs like “fly,” “teleport,” or “become invisible,” by contrast, are applicable in a broad range of situations.

What about roleplay? It’s true that Skill Verbs like “deceive” (Deception), “intimidate” (Intimidate), and “persuade” (Persuasion) are relatively frequent and useful. However, unlike weapon and armor-related Item Verbs, there’s no good reason why non-casters should be naturally better at using these verbs than casters. In fact, for Charisma-based casters like warlocks, sorcerers, or bards, the exact opposite is true!

This is, again, exacerbated by the fact that roleplay-related skills naturally rely on the same ability scores that a caster does. A warlock with an Intimidation proficiency has likely already heavily invested into Charisma as their primary ability score. A barbarian with an Intimidation proficiency, however, has to first pay their Strength and Constitution taxes before pumping up their Charisma. At best, giving non-casters a “roleplay skill boost” would allow them to reach the utility of casters in roleplay scenes, not exceed them!4

(When it comes to Social Verbs and Background Verbs, both casters and non-casters have equal access to things like making a good argument or choosing the Acolyte background, so we can basically disregard these.)

So, to sum everything up, we’ve got a game where:

Casters have more verbs than non-casters in combat, but non-casters somewhat make up for this by being more effective at using their shared verbs;

Casters have more verbs than non-casters in exploration, and non-casters’ preferred verbs are rarely useful; and

Casters have more verbs than non-casters in roleplay, and casters are usually better than non-casters at using some of their shared verbs.

This is a recipe for disaster.

How Did We Get Here?

In American comic books and Japanese manga, it’s not uncommon to see “casters” and “non-casters” specialize in different ways. “Casters” (such as Professor X in X-Men) are very good at doing complicated tasks that require lots of finesse and manipulation. “Non-casters” (such as the Hulk in The Incredible Hulk) are very good at doing simple tasks that require lots of brute force and power. Professor X can control the minds of a legion of hostile forces. The Hulk can punch through a building and then jump a mile away like the world’s angriest frog.

In a TTRPG system based on American comic books, there would be no war between casters and non-casters. Whenever you need someone to infiltrate the villain’s lair, you call Professor X. Whenever you need someone to smash the villain’s lair into tiny pieces, you call the Hulk.

But Dungeons & Dragons isn’t based on American comic books. It’s based on traditional fantasy media—and, specifically, the “swords and sorcery” model built on Conan the Barbarian (which distinguished “mundane” martial skills from “mighty and awe-inspiring” magical items and abilities) and Hammer Horror (which codified the modern conception of the divine “holy priest”).5

Now, Lord of the Rings—another source of inspiration for Dungeons & Dragons—made up for this by giving its non-casters lots of important titles and privileges. For example, Aragorn was the Last Chieftain of the Dúnedain, and Boromir, Legolas, and Gimli were all the children or heirs of important lords. As a result, they could use those noble titles to command the loyalty of lots of soldiers and obtain lots of resources fairly easily.

This is basically how old-school Dungeons & Dragons did it. As they got more powerful, casters got more powerful spells. Meanwhile, non-casters got things like lands, titles, and lots and lots of gold. And, for a time, this worked.

But The Lord of the Rings reveals the fatal flaw in this approach: Both Gandalf (who commanded the loyalty of the Eagles and the respect of the Rohirrim) and Saruman (who commanded an army of orcs and the tower of Isengard) also had access to lots of soldiers and resources. There’s really no good reason why non-casters should be able to become lords, generals, or landholders and casters can’t.

In a system built on dungeon crawls like Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, that’s a perfectly reasonable arbitrary distinction. But in a modern context, where lots of players and DMs are really invested in telling interesting and meaningful stories about characters they care a lot about, that line in the sand can’t survive. If non-casters can get fortresses, casters can get them too.

But that just leads us back to the original problem. When casters get spells like dominate person, non-casters can’t jump vast distances or break through walls like the Hulk to make up for it. Instead, like Aragorn, they’re stuck with a pointy sword, a shiny suit of armor, and not much else.

A Problem In Search of a Solution

Let’s take a second to organize the fundamental assumptions that led to this point:

Because most groups don't run an exhaustive standard adventuring day on every single in-game day, casters have lots of extra spell slots to spend on exploration and roleplay.

Because skills have less utility in most exploration contexts than spells, non-casters have relatively little to contribute, while casters have lots.

Because casters have an innate ability-score advantage, casters will almost always be better than non-casters at using roleplay-related skills.

Because most players prefer the traditional “swords and sorcery” concept, casters can specialize in order to access lots of extra verbs, but non-casters can’t.

We could change #1 by changing the types of campaigns we run, but most groups don’t want to. (The game, after all, should change to suit the players’ needs, and not vice-versa.)

We could change #2 by creating more opportunities to use exploration-related Skill Verbs, but that would just create more work for the DM. (It’d likely also feel unfulfilling, in the same way that adding foraging rules in order to let rangers ignore them feels unfulfilling.)

We could change #3 by giving non-casters a big boost in skill proficiencies and/or more ASIs, but doing so would feel inherently arbitrary (why are rogues better at persuading than bards?) and would also risk breaking 5e’s carefully balanced “bounded accuracy” system.6

Our only remaining lever, then, is #4. We could use this lever to remove casters’ extra verbs. (Skyrim and Dark Souls are examples of fantasy media that reduce casters’ power substantially.) But powerful spells like fly, telekinesis, and wish are too central to the Dungeons & Dragons brand to let go. As such, we’re left with a single remaining viable option:

Let non-casters cast spells.

The Wand Chooses the Wizard

Letting non-casters cast spells seems like a paradox. Non-casters are, after all, defined by the fact that they cannot cast spells. But non-casters in Dungeons & Dragons actually already have a way to cast spells: Item Verbs.

I’m talking, of course, about magic items.

Now, ordinarily, there are no restrictions on who can use a particular magic item. “Use Magic Item” is a verb that both casters and non-casters share. However, many magic items also carry certain prerequisites—for example, that they can only be used by the members of a certain class. This makes sense! It’s perfectly reasonable that only a cleric would be able to use a specific magical holy symbol (to channel their deity’s divine power) or that only a sorcerer would be able to use a specific magical amulet (to magnify and control their own inherent magic).

But, again, both casters and non-casters can pick up a sword or put on a suit of armor. The non-casters are better at using them, but any arcane property of a magical sword or magical suit of armor can be used equally well by a fighter or wizard. That’s because being a fighter doesn’t make you better at using magical swords; it just makes you better at hitting things with them.

The solution, then, is to create magic items that can be theoretically used by any class, but which, in practice, can only be used by a character who fits the unique profile of a “non-caster.” In Dungeons & Dragons, that means creating magic items whose properties can only be competently or safely wielded by a character with relatively high Strength, Dexterity, and/or Constitution scores.

Fortunately, western fantasy fiction has lots of examples of this! The “legendary weapon” trope has a long and respectable history across classic, pulp, and modern fantasy literature and cinema. Most D&D players don’t want Aragorn to punch through a wall with his bare hands. Most D&D players, however, wouldn’t mind seeing him break down a wall using an enchanted hammer—especially if that hammer were an ancient and powerful dwarven relic.7

To Each According To Their Needs

There is, inherently, no good narrative reason why a D&D party should find a magical sword that can only be used by someone with very big muscles, and not find a magical wand that can only be used by someone with a very big brain. The only reason why it’s a feasible solution at all is because, unlike noble lands and titles, well-tailored magic items do sometimes just drop from the sky.

It’s true that a legendary shortsword can be wielded equally as well by a rogue or a bard. It’s true that a legendary bow can be used by a druid as easily as a fighter or ranger. But we don’t need to give legendary shortswords or legendary bows out to bards or druids—only rogues, fighters, and rangers.

Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition is a fundamentally flawed game because it provides casters with a fundamental advantage outside of combat. Legendary, ability score-locked magical weapons are artificial aids that attempt to compensate for this.

And you don’t give artificial aids to people who don’t need them.

Does this approach require the DM to do more legwork to create appropriate magical items? Sure (though I’ve created nine already, which you can find here). Does this approach slightly change the Dungeons & Dragons fantasy by requiring the DM to give out more magical items (or at least more powerful magic items) to non-casters than casters? Sure.

But in a world full of tradeoffs, some sacrifices have to be made. If you don’t mind the status quo,8 or if all of your players all prefer to play the same kind of class, then you probably don’t need to make this addition.

But if your parties tend to include a mix of casters and non-casters, and the non-casters want to be able to contribute as much as the casters do?

Then maybe it’s time for a change.

Special thanks to Twi, PunchingPotato, Paintknight, and Bjarke the Bard for their feedback and suggestions regarding this article. Cover image credit to Wizards of the Coast.

DragnaCarta is a veteran DM, the author of the popular “Curse of Strahd: Reloaded” campaign guide, a guest writer for FlutesLoot.com, and the former Dungeon Master for the actual play series “Curse of Strahd: Twice Bitten.”

To read more of Dragna’s articles about D&D design theory, DMing tips & tricks, and principles of storytelling, subscribe now to receive new articles in your inbox.

To get Dragna’s hot takes and commentary, you can click here to follow him on Twitter.

The sole semi-exception to this general rule lies in class-provided tool proficiencies, such as thieves’ tools. However, because these tool proficiencies can also be gained from backgrounds (such as a thieves’ tools proficiency from the Urchin background), I do not consider them to be exclusive to non-casters.

Why not completely? Because high-level spell slots are way more effective than anything martials can ever hope to do. No matter how hard a fighter tries, they can never cause as much devastation as a cleric casting earthquake.

Non-casters also tend to have larger hit dice, which help them survive for longer periods of time on the front lines, but don’t actually tend to help them accomplish anything that casters couldn’t also do.

The same is true for knowledge-related skills (e.g., Arcana, History, and Nature) in the exploration context.

I was peripherally aware of Conan before writing this article, but had never heard of Hammer Horror before. Many thanks to my friend Twi for educating me on both.

For those who aren’t familiar with it, the concept of bounded accuracy is a mechanic that ensures that no part of the game is completely inaccessible to low-level players. For example, skill-check DCs in 5e are unlikely to go far above 20, but DCs in Dungeons & Dragons 3.5 could easily exceed 30.

To carry on the Lord of the Rings example, Frodo is uniquely capable because, as a hobbit, he’s one of the only ones able to safely wield the One Ring, a powerful ring of invisibility.

While it’s not traditional “fantasy,” the ending of the first Guardians of the Galaxy movie (which is less about “super-powered mutants” than “high-skilled muggles in a weird and wacky universe”) also features a group of doughty, strong-willed individuals able to control the power of a highly volatile magical artifact.

(Of course, the movie’s themes strongly suggest that any group of people working together could have done this, regardless of their strength or willpower. Thanos, the Infinity Gem-wielding villain of Avengers: Infinity War, might be a slightly better example.)

For an example of a non-western piece of media that also plays with this trope, see Kill La Kill, in which a spirited, strong-willed fighter is uniquely competent to master and release the true strength of a powerful artifact.

For example, because your casters prefer to optimize for combat instead of exploration or roleplay, because your campaign’s narrative usually prioritizes the non-casters over the casters, because your casters are audience members, or because your non-casters are happy to let the casters lead.

One factor that makes all this worse is that utility spells usually always succeed, whereas with the swinginess of d20 and the fact that skill checks are usually meant to be a single die roll, it can take quite a while for proficiency to mean much, compared to unskilled casters attempting the same challenge. Things like expertise and reliable talent help a little, but I’d say it’s too little, too late.

Also, much like it’s difficult (and for many people tedious) to fit the amounts of combat into an adventuring day that the system intended, I imagine it’s a challenge to fit the amount of meaningful skill checks into an adventuring day so the spellcasters limited resources start to matter.

> We could use this lever to remove casters’ extra verbs. (Skyrim and Dark Souls are examples of fantasy media that reduce casters’ power substantially.) But powerful spells like fly, telekinesis, and wish are too central to the Dungeons & Dragons brand to let go. As such, we’re left with a single remaining viable option:

> Let non-casters cast spells.

This resonated strongly with me. 4e did this with their versions of rituals, which 5e then butchered. Back when I was playing 3e, I even made a variant for that edition that added 4e rituals into it: https://dnd-wiki.org/wiki/Rituals_(3.5e_Variant_Rule)