This article is the second in a series about D&D 5e combat design theory. Subscribe to the Dragna’s Den Substack now to get future articles in your inbox!

In my first article in this series, I attempted to present a unified theory of 5e combat design—why encounters are easy or difficult, how the adventuring day works, and how DMs can structure their sessions and set players expectations to curate a particular kind of experience.

My central takeaway was that 5th Edition is fundamentally built to be a resource-management game—a game in which players must carefully expend and shepherd their resources, from spell slots to hit dice, and in which DMs must carefully work to exhaust those resources in order to cultivate a challenging experience.

Now, there are very good reasons to dislike this kind of gameplay. As Justin Alexander of The Alexandrian (who’s been analyzing TTRPG design theory longer than I’ve been a DM) excellently puts it:

This resource-management game—which, again, lies at the core of 5th Edition’s mechanical framework—is fundamentally at odds with the tactical, narrative, choice-making game that most DMs and players want to play. I mentioned this in my response to Justin’s thread:

Now, I had originally planned for this article to be the final publication in my series on 5e combat design theory. However, upon publishing my first article, I received substantial pushback on Twitter—not just from people who believed that my analysis was flawed, but from people who fundamentally objected to the concept of running D&D as a resource-management game.

Here’s the thing: I entirely agree with this! I don’t like the resource-management game, and I think most players don’t either. 5th Edition’s resource-management framework is, for most groups, a silly, unfun framework that either forces DMs to sacrifice some of their most beloved types of gameplay (such as climactic combat encounters) or forces players to sacrifice their preferred gameplay (such as meaningful agency in decision-making).

This is a system that tends to turn DMs and players into adversaries—in which DMs, in order to sculpt the kind of experience that they want to create, are ultimately forced to diminish the players’ ability to do the same.

Imagine that you have a next-door neighbor who keeps throwing rocks through your house’s windows. A scientist walks up and starts analyzing how large the rock has to be to break through the window, what kind of glass you should purchase to stop the rocks from breaking your windows, and exactly how you should rearrange your furniture to minimize the amount of property damage.

The solution isn’t to criticize the scientist. The solution is to stop your neighbor from throwing rocks.

Fortunately (for 5e DMs and players), there’s a way to change 5e’s mechanics that puts DMs and players on the same side. And fortunately (for me and the future articles I’ve outlined for this series), doing so doesn’t fundamentally change the nuts and bolts of how 5th Edition combat works—only how different combat encounters combine together to create a final "adventuring day." (It does force us to make some tweaks to our character sheets, though.)

Note that, if you're the kind of DM who enjoys running grueling and gritty dungeon-crawls that force players to carefully shepherd their resources, this article is not for you. (Your preferences are valid, and I highly encourage you to check out the first article in this series.)

If, however, you're the kind of DM who thinks that D&D is fun when the players are free to strategize and tell interesting stories instead of obsessing over logistics, then I hope that this article provides you with a helpful and relatively simple approach to modifying 5e accordingly.

Let’s begin.

I. The Type of Game We Want To Play

Let’s start by discussing the kind of gameplay that players usually want 5e to have:

Players like encounters that meaningfully challenge them, and dislike encounters that are trivial or impossible to overcome.

Players like using their cool abilities, and dislike either running out of their cool abilities or having to ignore their cool abilities in order to “save them for later.”1

Players like adventuring days that allow them to focus on immersing themselves in the story the campaign is telling, and dislike adventuring days that force them to focus on the mechanics the system is using.

Players like adventuring days that allow them to exercise a lot of freedom in how they approach or solve their problems, and dislike adventuring days that restrict that freedom.

DMs tend to be fairly similar:

DMs like encounters that meaningfully challenge the players, and dislike encounters that are instantly defeated or lead to TPKs.

DMs like using their cool monsters, and dislike having their cool monsters quickly and unceremoniously defeated.

DMs (especially in 5th Edition) like telling flexible, set piece-based stories that focus on the choices that players make, and dislike telling combat-treadmill stories that focus only on how many monsters the players can kill.

Now, the way 5th Edition is set up automatically forces us to put many of these priorities at odds—for example, in order to meaningfully challenge players with climactic encounters, DMs are forced to severely curtail players’ freedom and immersion in order to control the resources they have at their disposal.

If you’re the kind of DM who dislikes running lots of low-difficulty encounters, this system also forces you into running only certain kinds of adventuring days. For example, you can’t run an adventuring day that includes lots of deadly encounters because your players will run out of resources before lunchtime. As such, if you prefer running deadly encounters, you’re limited to running one to three per day maximum.

In both cases, this is because long rests are bad.

II. Long Rests Are (Mostly) Bad

Imagine you’re a teenager and your parents go on vacation and leave you at home.

You, naturally, won’t survive unless you have food to eat, access to transportation, and so on. Because these things cost money, your parents leave you with some money to pay for it.

Let’s assume that a single meal, on average, costs $10. If your parents go away for a week, you’ll need $210 to cover the cost of food (7 days • 3 meals per day • $10 per meal). “Don’t spend it all in one place!” they tell you with a wink.

But what if you spend the first three meals buying nothing but $70 steaks? Suddenly, you have nothing to eat for the rest of the week! What if you spend the whole week living off of $1 ramen in order to spend the money on an XBox? Suddenly, your parents come home and find that you have scurvy.

Now, if you’re a mature teenager who knows the importance of nutrition and understands how to budget their money, you’ll probably be fine. But sometimes, we just want an expensive meal or a shiny new toy. That’s part of the fun of spending money! And in either case, most people don’t find budgeting fun.

D&D is a game, and games should be fun. Ergo, D&D should allow players to buy expensive meals, buy shiny new toys, and avoid the need to budget their money.

So what’s the solution?

Let’s go back to our teenager hypothetical. Your parents have a problem: They keep going on vacation and finding that you’ve either starved to death or gotten scurvy. This, naturally, is very inconvenient for them.

Why? Because you specifically did what they told you not to do: spending all of the money in one place.

Fortunately, they have a way of making this impossible: by chopping up your budget into smaller, discrete pieces. Instead of giving you all of the money upfront, they create an account that has $10 in it. Every time you need to buy breakfast, lunch, or dinner, they check the account to see how much money is in the account. If it has less than $10 in it, they put just enough money in to bring it back up to $10.

If you spend $1 on ramen, then you don’t get back $9 to save for an XBox—you get another $1. And you can’t spend $70 on fancy steaks because there isn’t $70 in the account.

In D&D, however, we can’t store ability resources in bank accounts.

We can store them in short rests instead.

III. Short Rests Are (Mostly) Good

Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition got a lot of things wrong, for which it understandably caught a lot of flack. (More on this below.) But it also got a lot of things right. The biggest thing it got right was the abolition of most long-rest features like spell slots and their replacement with encounter powers.

In 4th Edition, you can still cast fireball, but you can only do it a limited number of times per encounter. Once you finish an encounter, you automatically get that fireball back for the next one.

Now, there were some valid objections to this model. Notably, the scope of an “encounter” is inherently arbitrary. If I spend one round fighting two goblins, how is that meaningfully similar to ten rounds spent fighting a vampire? Moreover, if I defeat those goblins and then start fighting a vampire six (or twelve, or thirty) seconds later, is that one encounter or two? The answers to these questions are inherently arbitrary!

This approach “gamified” D&D’s spells and abilities in a way that made many players feel uncomfortable. Most of us play D&D in order to tell a story, not to play a “game” like Settlers of Catan or Warhammer 40K. The concept of “encounter powers” is inherently antithetical to that desire.

This issue was further exacerbated by the fact that spell slots are largely fungible, while “encounter powers” are not. If a wizard can cast fireball and fly in the same encounter, why can’t that wizard instead choose to cast fireball twice? The division felt artificial and generally diminished player freedom.

5th Edition fixed this by turning most “encounter powers” into “short-rest features,” and turning the remaining encounter powers back into “long-rest spell slots.” (The Warlock, who regains spell slots on a short rest, and the Monk, who regains ki points on a short rest, are the sole exceptions.) 4th Edition also had “daily powers,” which 5th Edition just turned into high-level spell slots or long-rest features.

This had the benefit of removing the “video-game” language that made players so uncomfortable, but had the drawback of giving players who played long-rest classes lots of money to spend on fancy steaks or XBoxes.

It also replicated the problem on a smaller scale with short-rest classes. Because 5e’s short rests take a full hour (in contrast to 4e’s five-minute short rests), most parties can’t afford to take a short rest between every single encounter. In our teenager hypothetical, a short-rest class who gains up to $30 every day instead of $10 at every meal might not be able to afford a $70 steak. However, they will happily burn $30 at a nice upscale café for breakfast—and then go hungry at lunch and dinner.

Now, the nice thing about encounters in a short-rest system is that you can make them as challenging (i.e., “expensive”) as you like. It doesn’t matter if your players have one spell slot or six to spend on them, so long as they can get them back almost immediately afterward. The question is how you can make sure they get them back almost immediately afterward.

It’s rarely possible to take a one-hour break after finishing a combat encounter. But it is usually possible to take a five-minute break.

Here, then, is the first step of the solution to eliminating 5e’s resource-management game: replace all long-rest abilities (including spell slots) with short-rest abilities, and decrease the length of short rests from sixty minutes to five minutes.2 (We’ll talk more about what this looks like in practice below.)

This has two additional benefits:

Because long-rest caster classes (such as wizards) can no longer “go nova” and outshine non-caster or short-rest caster classes (such as fighters or warlocks) in a single encounter, non-caster classes are less readily outshined by caster classes, and don’t need a certain number of encounters or short rests per day to reach “parity.”

Because short rests are more accessible, all classes have more freedom to use their short-rest spells and abilities (such as a barbarian’s rage, a druid’s wild shape, or a fighter’s second wind) outside of combat, removing the need for combat encounters to “compete” with non-combat ones.

But what about hit points?

IV. Lessons From 3.5

The concept of using short rests to regain hit points was, generally, popularized by 4th Edition. In Dungeons & Dragons 3.5, once you lost hit points, there were only two ways to regain them: magical healing (which either consumed magic items or spell slots) or ordinary healing (which restored a limited number of hit points—not all!—each time you took a long rest).

In a party that doesn’t have access to lots of magic items or spell slots, this system naturally promotes adventures that create space for lots of downtime. After all, if it takes your PCs a full week to regenerate his hit points to full, you’re going to want to make sure that they can reliably go on sabbatical every time they defeat a new villain.

But many DMs and players don’t like systems with lots of downtime. Even those that do make space for downtime also tend to enjoy running lengthy, high-stakes adventures with lots of climactic battles that will inevitably heavily tax the PCs’ hit points. In both cases, magical healing has to step up to fill the gap—which, in practice, meant that DMs had to provide lots of magic items (such as potions of healing) and lots of NPC spellcasters that the players could purchase healing from.

In 5th Edition, Wizards of the Coast consciously decided to step back from this model. Instead, 5e’s Challenge Rating and encounter-building systems assume that the players have no magic items. (A future article in this series will discuss how giving players magic items impacts combat outcomes.) As a result, 5e had to fill the void somehow, and it did so by allowing players to regain variable numbers of hit points during a short rest, and all of their hit points during a long rest.

The good part of this system is that it allows players and DMs to run the kinds of adventures that they enjoy without forcing the DM to provide lots of healing potions and NPC clerics. The bad part of this system is that it retains part of the resource-management game that has caused 5th Edition tables so much grief.

While players (usually) can’t consciously spend their own hit points or hit dice in combat , DMs still have to account for players’ total health resources when planning the adventuring day. This, in turn, forces you to do things like including a certain minimum number of encounters per day and including a certain number of short rests between those encounters.

Now, if you’re the kind of DM who likes grittier adventuring days that slowly wear the PCs down and dislikes “superhero”-style games where the PCs can take on an infinite number of encounters per day, you might be willing to make this tradeoff! But I believe that it doesn’t have to be a tradeoff at all.

Let’s remember the kind of experience most players and DMs want: an adventuring day that allows for lots of DM freedom in creating encounters and lots of player freedom in confronting them. Most DMs also want an adventuring day that allows encounters to slowly wear their players down over the course of the day. We want a framework where the PCs are never likely to die after finishing a long adventuring day, but we do want a framework where their last encounter feels noticeably more taxing than their first.

If we allow PCs to indefinitely regenerate all or some of their hit points every time they take a short rest, then they’ll never get worn down. However, if we limit the amount of times PCs can regenerate their hit points, then they’ll inevitably get tired and die. The solution is to limit the number of times the PCs can regain hit points, but allow them to control how frequently they need to do so.

To do so, we can split “hit points” into two health pools: “hit points” and “will points.”

Hit points reflect real, physical injuries. Here, they work almost the same way as they always have: If you hit zero hit points, you fall unconscious and eventually die. You regain all of these hit points whenever you take a long rest, and can restore some of them by using magical healing. (Notably, though, you can’t regain them by taking a short rest.)

However, in order to damage a creature’s hit points, that creature's opponent needs to first deplete their will points. Will points reflect the natural wear-and-tear of battle—muscle strain, exhaustion, and focus. As soon as a creature runs out of will points, they’re going to start getting sloppy and making mistakes—which is enough for their opponent to inflict a real injury.

(Funnily enough, this concept of will points actually follows the concept of hit points as originally conceived in Fifth Edition, which describes hit points as "a combination of physical and mental durability, the will to live, and luck.")

Here’s the key point: Like hit points, a creature can restore their will points by taking a long rest. However, they can’t restore their will points by using magical healing. A creature can only restore their will points by taking a short rest—a five-minute breather.

Notably, this applies to both monsters and PCs. As such, both PCs and monsters gain an effective boost to their hit points by gaining will points, which function as a second health pool.3 (If you’re a DM who likes running battles with solo boss monsters, this is a great way to help them survive for a longer number of rounds, as well as a way to help avoid death-spiral TPKs.)

However, unlike monsters, PCs have to fight in several different battles every day. As such, over the course of the day, PCs will almost always have all of their will points whenever they start a new encounter, but will slowly run out of hit points with each new fight.4

This also removes the need for the DM to precisely calibrate when and where the PCs get to rest, and instead creates new tactical gameplay for the PCs. When you run out of will points, will you choose to remain and risk a real injury? Or will you temporarily retreat and take cover—or flee from battle entirely?

This also allows DMs to better convey the difficulty of an encounter to their players in real-time. If the players inflict a real injury on a monster after a single round of attacks, that’s a sign that the monster has relatively few will points and is fairly weak. If, however, after three rounds of combat, the players have failed to inflict any real injury, that's a sign that the monster has relatively many will points and is actually fairly strong!

V. Lessons From 4th Edition

In addition to the creation of “encounter powers,” 4th Edition also did something very interesting: It introduced the concept of “daily powers.” These were generally abilities that were too powerful to use in every encounter, but which could turn the tides in a very difficult one.

Now, unlike encounter powers, these abilities felt far more organic. After all, it makes sense that you can regain the ability to do certain things by getting a good night's sleep. However, 5e generally abolished this in favor of limiting the number of high-level spell slots that casters can use each day. (For example, a 20th level wizard will only ever have two 6th-level spell slots and four 1st-level spell slots per day, excepting the use of arcane recovery.)

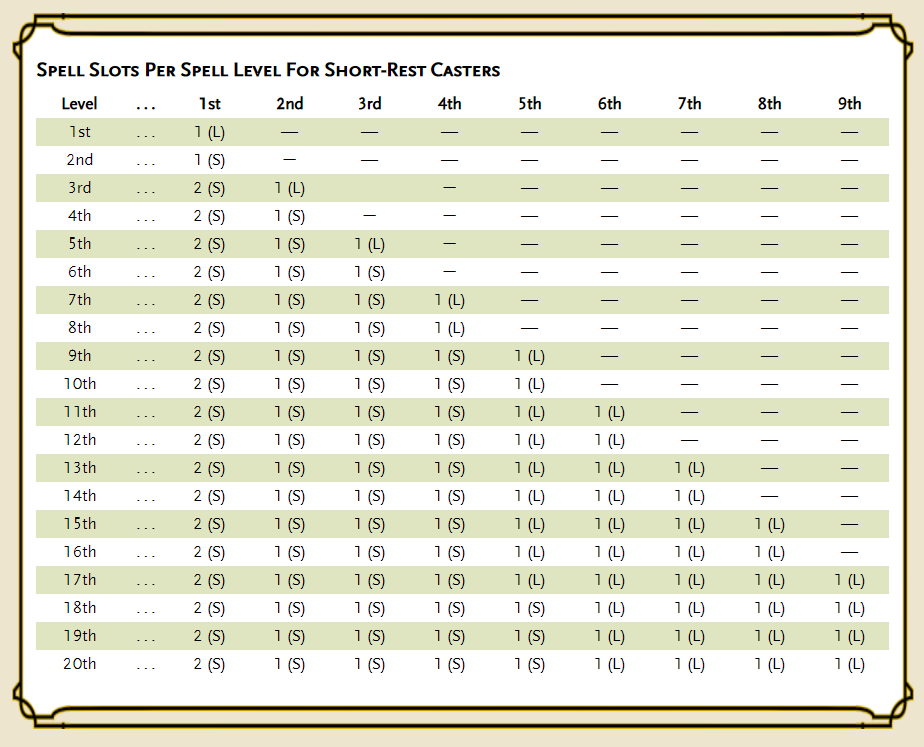

Now, even if we're allowing PCs to regain spell slots on a short rest, it can be dangerous to do so for high-level spell slots—just imagine a wizard casting meteor storm nine times in nine encounters! Accordingly, we should adapt 4e's concept of "daily powers" to limit the use of high-level spell slots that risk overrunning our encounters.

Here's the rule: At any given level, divide the number of spell slots you have for a given spell level by three.

If the result is equal to 1, you regain one spell slot of that level upon taking a short rest.

If the result is greater than 1, you regain two spell slots of that level upon taking a short rest.

If the result is less than 1, you regain one spell slot of that level upon taking a long rest.

In other words, if you have:

four spell slots under the traditional system, you have two spell slots instead, which recharge on a short rest;

three spell slots under the traditional system, you have one spell slot instead, which recharges on a short rest; and

less than two spell slots under the traditional system, you have one spell slot instead, which recharges on a long rest, not a short rest.5

(Note that these changes do not affect warlocks, who are already short-rest casters.)

Don't feel like doing the math every time? Here's an easy table for you and your players to reference, marking short-rest spell slots with (S) and long-rest spell slots with (L).

This does, of course, have some knock-on effects for some assorted long-rest features. For example, a wizard's arcane recovery is now basically useless for regaining low-level spell slots, which now come back on every short rest automatically. As such, instead of allowing wizards to use arcane recovery on a short rest, let’s change it so that they can use it as an action instead.

These changes also impact features that can be used a certain number of times per day. For example, a bard can use their bardic inspiration feature a certain number of times per day equal to their Charisma modifier, and regains all expended uses on a long rest. However, the 5th-level feature font of inspiration allows a bard to regain all expended uses on a short rest instead.

Generally speaking, most bards will have a Charisma modifier of +3 or +4 from levels 1 to 7, and a modifier of +5 starting at level 8. Under 5e’s long-rest system, that means a bard below 5th level can use bardic inspiration three or four times a day, a bard at 5th through 7th level can use it nine or twelve times a day, and a bard at 8th level or above can use it fifteen times a day.

Just like spell slots, let’s divide these by three:

By default, a bard can use bardic inspiration once per short rest.

At 5th level, the font of inspiration feature allows a bard to use bardic inspiration three times per short rest.

At 8th level, this increases to five times per short rest.

Here’s the fun part: This means that, once our bard hits 8th level, they’ll be able to use bardic inspiration—their core class feature!—on every round of almost every combat. Notably, this is something they could have done anyway, assuming they budgeted properly. But now, they don’t have to budget; it’s just a default part of the class experience.

And I think that’s pretty cool.

VI. The Problem With Healing

By allowing casters to regain spell slots on a short rest, we’ve created a fundamental problem: Because a caster can spend a spell slot to cast a healing spell like healing word, a caster can spend all of their spell slots on healing magic, take another short rest, and repeat the process indefinitely.

As a result, the distinction between “will points” and “hit points” becomes meaningless (because a PC who knows healing word can cast it indefinitely every time the party finishes an encounter). A party with a PC capable of healing magic will almost never arrive at an encounter with less than full health as long as they can take a short rest.

4th Edition solved this problem by forcing the recipients of healing magic to spend “healing surges”—4e’s functional equivalent to hit dice—in order to receive any benefits. (The logic makes a certain amount of sense—the magic is consuming your body’s nutrients and resources in order to fuel any regeneration. Too much healing could kill you by consuming all of your body’s energy and stopping your heart. This is why recipients of magical healing in fiction often become temporarily ravenous shortly thereafter—they need to replenish lost fat reserves and nutrients that were used to regrow tissue and replenish blood.)

Fortunately, 5th Edition also has “healing surges” in the form of hit dice—and now that short rests don’t allow PCs to spend hit dice to regain hit points, we’re not actually doing anything with them.

Instead of allowing healing word to restore an amount of hit points equal to 1d4 plus the caster’s Wisdom modifier, let’s change it to instead allow its target to spend and roll hit dice, as they would have during a traditional 5th Edition short rest. (Unlike the traditional system, a creature regains all of its hit dice upon finishing a long rest, rather than half of its maximum.)

For every die of healing—or for every five hit points of healing—that a target would have received from a healing spell or feature, the target instead spends and rolls one of their own hit die, adding their Constitution modifier to each dice roll.

For example, if a cleric cast a 2nd-level healing word on a 3rd-level fighter with +2 CON, the fighter would need to expend and roll two of their three d10 hit dice. If the fighter rolled two fives, they would regain 10 hit points plus an additional 2 hit points for each die rolled, for 14 hit points total.

I’ve compiled an (exhaustive) list of spells and a (non-exhaustive) list of features that would need to be tweaked in order to implement this change, which you can find in the footnotes.6 (Note that any spells of 6th level or higher have not been changed. That’s because, under our new spell-slot system, a caster can only ever regain those spell slots on a long rest, rather than a short rest.)

While a small complication, this change does have one major advantage: Because targets are spending their own hit dice instead of the dice set by the spell, it’s now more advantageous for casters to heal characters with bigger hit dice and Constitution modifiers (e.g., fighters and barbarians) than characters with smaller hit dice and Constitution modifiers (e.g., wizards and sorcerers). Because martial classes generally have bigger hit dice and higher Constitution modifiers than casting classes, this is a relative buff to martial classes (who should now receive a larger share of healing) over casting ones.

However, if a caster doesn’t want to use their spell slots on healing spells—or if a party doesn’t want to include any casters at all—they’re still no worse off! Instead of spending their spell slots on post-combat healing, they can spend those spell slots or other resources on mid-combat damage, control, and support instead.

VII. A Modest Proposal

In sum, here are the changes I propose:

Short rests take five minutes instead of one hour. (Long rests are still eight hours.)

All long-rest abilities and spell-slots are changed to be short-rest abilities and spell slots instead. (To accomplish this, we calculate the number of times a character would be able to use that ability or spell slot per day after a long rest under the traditional system, and divide by three.)

Creatures have two pools of health: hit points and will points. PCs can restore all of their will points by taking a short or long rest, but cannot restore will points by using magical healing. PCs can restore hit points only by taking a long rest or by using magical healing.

A creature’s total number of hit points is equal to a creature’s ordinary amount of hit points. A creature’s total number of will points is equal to the average sum of half of the creature’s hit dice (rounded down), plus the creature’s Constitution modifier multiplied by the same number of hit dice. (For example, if I have 11d8 hit dice and +2 to Constitution, I have 5 ⋅ (4.5 + 2) = 33 will points.)7

The recipient of a magical healing spell or feature must instead spend and roll a number of hit dice equal (a) to the number of dice that the caster would have rolled or (b) one-fifth the number of set hit points that they would have gained (rounded down). They then add their Constitution modifier to each die rolled (if any), and regain hit points equal to the result.

A creature regains all of its hit dice upon finishing a long rest, rather than half of its maximum number of hit dice.8

Here's a short list of the impacts I expect these changes to have:

Because every encounter is largely independent of the others, DMs will have full freedom to build challenging, complex encounters, and will be able to include (to a certain extent) as many or as few encounters per day as they like while still slowly wearing PCs down over time.

Because PCs are unable to “go nova” on a single encounter, DMs can use the labels provided by 5e’s original encounter difficulty system (“Easy,” “Medium,” “Hard,” and “Deadly”) in a meaningful way to create combats of varying difficulty. (For example, the party will need to act intelligently and efficiently in order to defeat a “Hard” encounter, will not need to work especially hard to defeat a “Medium” encounter, and is at a real risk of defeat in a “Deadly” encounter.)9

Because PCs have (almost) the same number of resources in nearly every encounter, players will have full freedom to use as many or as few of their abilities as they like in each encounter, but will have the incentive—and the freedom—to approach encounters tactically and strategically in order to avoid losing hit points that can’t be regenerated naturally.

Because PCs have reliable access to their core class features in nearly every encounter, players will be able to live out their full character fantasy in every battle—including the ability to cast cool, fun spells instead of lame, boring cantrips.

Because PCs have a limited number of spell slots that they can use, and those spell slots refresh after nearly every combat, players have to make fewer tradeoffs in battle, reducing “choice paralysis” and making combat faster.

Because PCs have will points instead of short-rest healing, their resilience is front-loaded instead of back-loaded, making them better at surviving challenging battles—especially 1st-level PCs—and making player death spirals more difficult. Meanwhile, it’s easier for DMs to use level-appropriate solo boss monsters, because the addition of will points and the inability for PCs to “go nova” will make those monsters more difficult to kill.

Because PCs can’t regain hit points on a short rest, and because will points are a powerful signal of encounter difficulty, players will feel less invulnerable in combat, and will be more likely to prioritize avoiding monsters’ attacks or fleeing battle entirely when faced with challenging combats.

Because a PC can only regain hit points through a long rest or magical healing, the common strategy of using healing word to “yo-yo” a character between 0 hit points and 1 hit point during combat is greatly nerfed (because the character will only be able to regain will points, not hit points, during their next short rest.)

Notably, there's a long list of things about 5e's combat system that this doesn't change, including:

Why solo boss battles are (still) somewhat fundamentally flawed. (We'll talk about this in the next article, as well as how to fix them.)

The impact of magic items, party composition, and spell choice on encounter difficulty. (Ditto.)

The ways in which PCs can use battlefield tactics (such as cover or positioning) and strategy to overcome encounters. (Because we've abolished the resource-management game, this is suddenly much more important.)

In Conclusion

Is this article entirely comprehensive? Almost certainly not—there are many class features and abilities that would require some minor to moderate tweaking under this framework.

Notably, however, I believe that this approach has a lot of advantages, largely centered around the freedom and flexibility it offers to your table.

Compare it, for example, to the Gritty Realism rest variant provided in The Dungeon Master’s Guide, which extends short rests to twenty-four hours and long rests to a full week. This method, unlike Gritty Realism, allows DMs to create campaigns that don't offer long periods of reliable downtime, and doesn't require tables to rebalance individual spells with long durations (e.g., mage armor).

Meanwhile, while clever 5e DMs can compensate for inefficient encounter-building or resource-management by fudging dice rolls, doing so doesn't promote player agency—instead, it sacrifices player agency inside of individual combat encounters in exchange for promoting player agency throughout the adventuring day as a whole. By contrast, this method allows DMs to create encounters that are less likely to lead to TPKs or easy victories—both because “Deadly” encounters are actually deadly (which means DMs will know to avoid them), and because “Medium” encounters are actually of moderate difficulty—while giving players full control of the encounter’s ultimate outcome.

Ultimately, that's what I care about: empowering players and DMs to play the kinds of games they most enjoy. 5th Edition, historically, has done a terrible job of this, and has succeeded only in spite of itself. This framework, I hope, changes that.

Obviously, this is an approach that can always use more playtesting. I know I'll be trying it out in my next campaign.

Will you?

This article is the second in a series on 5th Edition combat design theory. Future posts will discuss problems with solo boss-monster encounters, the role of magic items in altering an encounter’s difficulty, and the impact of party composition, battlefield tactics and character-build optimization. Thank you for reading, and make sure to subscribe to receive future articles in your inbox!

Special thanks to Twi, PunchingPotato, Paintknight, Flutes, Starless, vanguard2k, nyckelharpan, Mortian, wakashirimi, Stef, Humanfarmerman, and Bjarke the Bard for their feedback and suggestions regarding this article. Cover image credit to Wizards of the Coast.

DragnaCarta is a veteran DM, the author of the popular “Curse of Strahd: Reloaded” campaign guide, a guest writer for FlutesLoot.com, and the former Dungeon Master for the completed actual play series “Curse of Strahd: Twice Bitten.”

To support Dragna’s work and access perks like DMing workshops, homebrew content, personal campaign advice, and a supportive Discord community, you can click here to join his Patreon.

To get Dragna’s hot takes and commentary, you can click here to follow him on Twitter.

It’s true that players can have a lot of fun by winning encounters after they’ve exhausted all of their resources. See “V. Lessons From 4th Edition” below for a discussion of “daily” spell slots, which allow PCs to still win by the skin of their teeth if they spend their biggest guns too early in the day.

Unlike the Dungeon Master’s Guide’s Epic Heroism rest variant, we leave the length of long rests unchanged.

The distinction between “hit points” and “will points” necessarily raises a number of questions, which I will attempt to answer here:

Mythic Actions and magical regeneration (such as a vampire’s regeneration feature) restore hit points only, not will points.

An effect that reduces a creature’s hit point maximum (such as a vampire’s bite attack) reduces their hit point maximum only, not their will point maximum.

A creature that gains another creature’s hit points (such as through a polymorph spell or the wild shape feature) gains that creature’s hit points, but has zero will points while transformed. (The transformed creature’s original will points can only be depleted once their transformation’s hit points are reduced to zero. Excess damage is carried over as usual.)

Spells and abilities (such as power word kill) whose effects are determined by their target’s hit points use their target’s hit points only, not their will points.

A creature that gains a fourth level of exhaustion will have its hit point maximum halved, not its will point maximum.

As a general rule, a spell or feature that specifically mentions “hit points” applies to “hit points” only, not will points.

Technically, it’s reasonable to expect that a monster might flee from combat, take a short rest, and regain its will points. Speaking personally, I’m fine with that—it successfully got away and should have a chance to meaningfully recover. If the PCs can do it, why can’t the monsters?

It’s worth noting that this change somewhat nerfs high-level casters. Instead of having two 6th- and 7th-level spell slots per day, a 20th-level caster will only have one of each. However, this is more than made up for by their ability to reliably cast a 5th-level spell in every encounter throughout the day. If the PCs take four short rests in a day instead of the traditional two, our 20th-level wizard is actually casting more 5th-level spells (and 4th, 3rd, 2nd, and 1st-level spells) than they would get to otherwise!

A comprehensive list of modified and non-modified healing spells is as follows:

Aid is unchanged.

Aura of Life is unchanged.

Aura of Vitality allows a creature to spend and roll up to two hit dice.

Cure Wounds allows a creature to spend and roll up to two hit dice. (This is a functional change made to distinguish cure wounds from healing word.)

Enervation allows its caster to spend and roll hit a number of dice up to to half the number of necrotic damage dice rolled.

Goodberry cannot be cast unless its caster spends two hit dice. (This is a functional change made for balance purposes.)

Heal is unchanged.

Healing Spirit allows a creature to spend and roll one hit die.

Healing Word allows a creature to spend and roll one hit die.

Life Transference allows a creature to spend and roll a number of hit dice up to twice the number of necrotic damage dice rolled.

Mass Cure Wounds allows each creature to spend and roll up to three hit dice.

Mass Heal is unchanged.

Mass Healing Word allows each creature to spend and roll one hit die.

Power Word Heal is unchanged.

Prayer of Healing allows each creature to spend and roll up to two hit dice.

Regenerate is unchanged.

Soul Cage is unchanged.

Temple of the Gods is unchanged.

Vampiric Touch allows its caster to spend and roll a number of hit dice up to half the number of necrotic damage dice rolled, rounded down.

Wither and Bloom is unchanged.

A non-comprehensive list of modified healing features is as follows:

A Life Cleric's channel divinity: preserve life allows any number of creatures within range to roll a total number of hit dice equal to the caster’s cleric level. The restriction limiting this feature to restoring a creature to no more than half of its hit point maximum is removed. (This is because magical healing cannot restore will points.)

A Paladin's lay on hands allows its user to expend and roll any number of their own hit dice in order to allow a creature to regain an amount of hit points equal to the result.

Note that the average of a die is equal to 0.5 plus half of its maximum value. For example, the average of a d6 is 3.5, the average of a d8 is 4.5, and the average of a d10 is 5.5.

The “half-of-your-maximum-hit-dice-per-long-rest” rule is an arcane vestige of 5th Edition’s resource-management game, and a mechanic that most DMs and players ignore. As such, I feel fairly comfortable removing it entirely.

In two simulations that Kobold Plus Fight Club found to be a “Hard” difficulty—involving a party of five 10th-level characters (a wizard, a bard, a paladin/barbarian, a warlock/rogue, and a sorcerer/rogue) against five chuul and one adult white dragon, respectively—the PCs were able to deal 400 damage to the chuul (60 percent of the total, including hit points and will points) and 119 damage to the dragon (40 percent of the total, including hit points and will points) by expending a 4th-level and 3rd-level spell slot (if available) over two rounds of combat. (In running these simulations, I used the Clockwork Mod Dice Calculator and the rules for adjudicating area-of-effect spells on p. 249 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide.)

Notably, because the casters in this simulation only used damage-dealing spells (such as fireball), rather than efficient support or control spells (such as suggestion or hypnotic pattern), this result suggests both that:

a party of characters facing a Hard encounter will somewhat struggle to win, but is very likely to eventually succeed; and

the use of battlefield tactics, pre-battle strategy, spell choice, and party composition can have a much larger impact on the outcome of combat than in RAW 5th Edition.

Very interesting and thought provoking ideas.

Is this just a theory or did you have a chance to playtest it? I am curious to hear actual feedback from players and DMs that tried this.

Few initial thoughts.

First, Will points seem to be another version of Stamina points and the like that we saw in some of the 3/3.5 and Pathfinder 1E optional rules and which was a core part of D20 Star Wars and Starfinder. Lots of other systems have had a version of it too. I think it's a good idea, though I do think that the massive amount of healing available in baseline 5E kinda made it a moot point. Under your proposed system it seems like PCs would be going into almost every encounter at max capacity, which does seem to be what a lot of groups gravitate toward. But if that's the goal, why not just say PCs start every encounter topped off?

Second, I don't see how this prevents casters from going nova at all, in fact I would argue it encourages it. Even if some spells are Long Rest and some of Short Rest, you are still dramatically increasing the casting capacity of any caster. Why wouldn't they go nova on every encounter if they know they can just rest for 5 minutes and get the majority of their spells back?

Third, this increases combat length rather dramatically as you're increasing everything's hit points without increasing the capacity for damage dealing. Doing some of the cool things we want to do in combat is even harder now because enemies have a big pool of Will points that have to be hacked through first before you even do real damage. Downing a low HP monster in one hit becomes much rarer like this. And ultimate the party is going to spend more resources on each encounter to resolve it. It seems like this would encourage players to be more frivolous with their resources and less likely to retreat from combat or try to find another way to resolve an encounter because they can go so much longer and know they can get the majority of their resources back after every encounter.

Finally, tieing HP healing to HD I think is inherently limiting, as the max healing any character can receive in a day is basically equal to their HP (assuming all rolls are average). This ultimately caps how many encounters a group can have in a day far more than the RAW rest system does I think. Fighter types for instance tend to take far more damage than anyone else and to need the most healing. It's not unusual in the typical adventuring day for a front liner to have taken many times more damage than their max HP over the course of the day thanks to healing. Now, you've limited how many encounters a melee type can have and made them a resource sink; RAW they have a pool of healing to draw upon from their allies' spells in addition to their HD that could be used in a short rest, under your proposed system now both of those resources are limited by the other and use each other, meaning that fighter types have LESS of the primary resource they need for adventuring over the course of a day than they do raw. One possible way to address this is to switch Will Points and Hit Points; make Will Points the much larger total and Hit Points much smaller. That would make HP damage less frequent but also far more dire, and would make HD much less limiting to how many encounters melee types could have.

I hope you don't take my critiques in the wrong spirit, I find this fascinating and enjoy exploring this topic and your insights into it:)