According to game design theory, games involving class-based tactical combat traditionally tend to invoke a number of expected class “roles”:

Some classes are tanks. A tank’s role is to “take damage for the group, protecting the others from being attacked.” A tank’s job is “to keep the monster's threat or attention on them, preventing the monster from attacking others in the group, who are often less armored and less able to take the damage from the monsters.”

Other classes are DPS (“damage-per-second”). The job of a DPS “is to kill the monsters”—to “dish out powerful damage without overwhelming the group's tank and causing the monsters to attack you.”

Other classes are crowd control. Their job is to “limit an opponent’s ability to fight,” and their abilities are used to “temporarily reduce the number of mobs that the group fights at once.”

Other classes still are buffing support. They “add a temporary effect to friendly players or party members,” which can “add abilities or enhance statistics, creating a more powerful character.”

Finally, some classes are healers. Healing is exceptionally underpowered in Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition, with the sole exception of the Life Cleric and Celestial Warlock subclasses, and so we won’t be discussing it today.

While Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition is not, of course, a game all about combat, it’s indisputable that combat plays a heavy role. Each class, in turn, has unique strengths, weaknesses, and abilities that—at least in theory—would appear to give them unique roles from the list above. For example:

Barbarians, due to their rage ability and exceptionally large health pool, are classic tanks. The same is true for fighters, who have a high AC, good saving throws, and the second wind ability.

Rogues, due to their extra sneak attack attack damage, are clear DPS. The same is true for paladins, whose smite ability gives them access to potentially immense nova damage.

Wizards, with such spells as hypnotic pattern, hold person, and sleep, are clear crowd control. The same is (potentially) true for monks, whose stunning strike can allow them to paralyze targeted foes, and whose flurry of blows can KO multiple smaller mobs per round.

Bards, with their bardic inspiration and spells like heroism or faerie fire, are exceptional buff support. That’s doubly true for clerics, who have access to spells like bless, shield of faith, and sanctuary.

This is all very good in theory—but in practice, it doesn’t hold up.

To Tank or Not To Tank

Let’s start with the ostensible tank classes—barbarian and fighter—as an example. According to Wikipedia:

“Tank characters deliberately attract enemy attention and attacks (potentially by using game mechanic that force them to be targeted) to act as a decoy for teammates. Since this requires them to endure concentrated enemy attacks, they typically rely on a high health pool or support by friendly healers to survive while sacrificing their own damage output.” (emphasis added)

In a video game like League of Legends or World of Warcraft, the game’s AI will often exercise precious little tactical skill. A clever tank can place themselves as close to the monsters as possible, thereby triggering the monsters’ “aggro” and drawing enemy fire automatically. It’s a simple, yet reliable algorithm.

In a video game, this works because we don’t expect the enemy mooks to be “real”—they’re pieces of code, to be manipulated for our amusement. But in a tabletop role-playing game like Dungeons & Dragons, enemy combatants are, at least ostensibly, living, breathing, thinking creatures.

Why would a goblin shoot the nearby fighter when it can instead shoot the low-hit point wizard who’s laying waste to its kin with fireballs and lightning bolts? Why would a ghoul attack the tough-and-stringy barbarian when it could instead lunge for the unarmored-and-squishy sorcerer standing a few steps behind her?

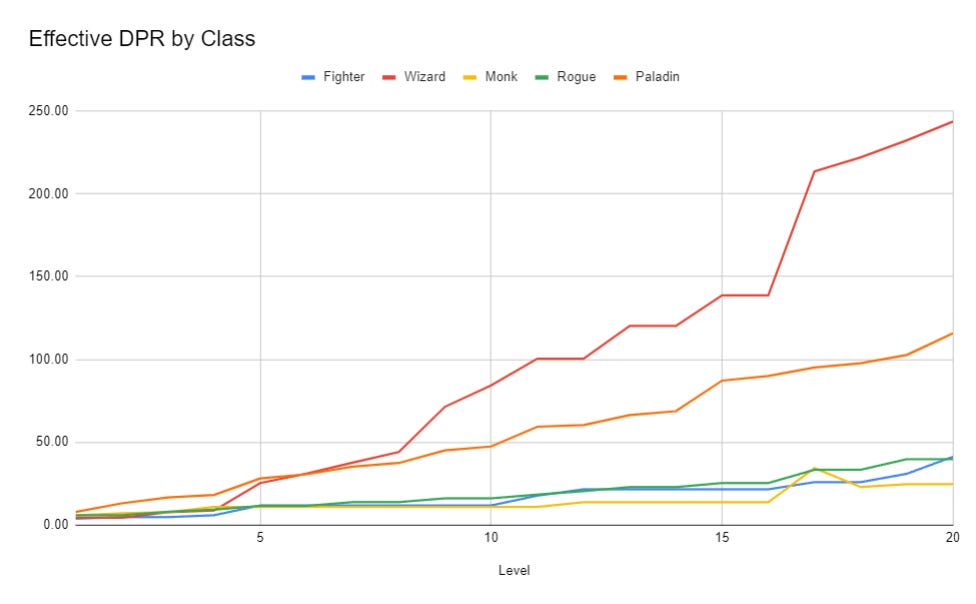

It’s not because the fighter or barbarian are doing more damage and therefore need to be “dealt with” first—once you hit Tier 2, the wizard’s effective DPR far exceeds them both in any encounter with four or more enemies!1

This chart also lays bare a similarly stunning truth: Not only is the wizard (the “crowd control” class) out-damaging the tanks (fighters and barbarians), they’re also out-damaging the DPS classes (rogues and paladins). There’s no reason not to attack the wizard first!

Now, it’s true that the wizard is far more fragile than both the tanks and DPS classes. Here’s a chart comparing each class’s effective hit points:

The wizard, as expected, comes last.2

But let’s think about this for a second: Our wizard is, as expected, our squishiest PC. Yet, unless they take the Sentinel feat, our fighters and barbarians usually have no real way to prevent enemies from attacking the wizard if they want to. That’s because 5th Edition martial classes generally have no way to force enemies to attack them, or to punish enemies who attack other PCs.3

So what’s a DM to do?

You can try to divide monster damage equally among casters and martials, or even prioritize the casters first. The casters will cast some spells, die in a blaze of glory, and leave the rest of the fight to the martials. In theory, this is a natural way to balance out casters’ access to powerful magic. It forces Concentration checks, encourages casters to choose their positioning wisely, and encourages casters to save their most dangerous spells for last, lest they incur the monsters’ wrath.

Now—again, in theory—this works for some groups! The casters will nod sagely, agreeing that it’s only right and good for smart monsters to Shoot The Mage First. In some cases, those casters will accept repeated and regular KOs without complaining.

In practice, though, most casters will instead choose to learn mage armor and shield, spam misty step or fly or polymorph to keep themselves safe, and generally learn to be their own tanks. Those that don’t will—fairly quickly—get frustrated with spending most combats unconscious (remember—martials generally have no way to actually stop monsters from targeting the casters!), and subsequently ragequit.

So that’s not a great strategy. What else can DMs do?

You can also try to create natural chokepoints for your tanks to occupy, forcing the monsters to attack the martials first before they can get to the casters. In theory, this is a great way to encourage and reward tactical combat!

In practice, this severely limits the kinds of battle maps you can use, punishes martials who would prefer to plunge into melee instead of holding back, and forces tanks into a boring, one-note battle routine.

You can also take the most common option: The monsters can attack the casters, but the DM commands them to arbitrarily choose to attack the martials instead. Once or twice per round, a goblin might send an arrow shooting toward the wizard, but the vast majority of attacks will splatter harmlessly off the fighter’s armor or the barbarian’s Rage.

Why? Because, in many playgroups, the martials are easy scapegoats for the casters’ bad decisions.

A Sacrificial Lamb

Let’s back up a bit. When your players sit down at the table, they all choose a class to play:

“Wow,” says the Fighter. “I like the idea of holding a sword and wearing armor. Sounds like a great balance of offensive and defensive capabilities!”

“Jock,” sneers the Wizard. “I’m going to choose the class with phenomenal cosmic powers instead.”

“But,” pipes up the Rogue, “What about your tiny health pool? You’ll go down in, like, three hits!”

The Wizard turns and flutters their eyelashes at the DM. “Oh, don’t worry,” the Wizard says. “I’m sure nothing like that would possibly happen. Fighter wanted to take lots of damage, didn’t they?”

The Fighter looks up from their character sheet. “What?”

“Excellent!” the Wizard says cheerily. “Then it’s settled.”

The wizard could have, but did not, choose a class with a reasonable amount of survivability. Instead, the wizard—understandably—chose a class with lots of punchy, powerful, flashy magical spells and a very very squishy body.

When a fighter takes damage that could have easily been dealt to the wizard, the fighter isn’t “being a tank.” The fighter isn’t doing anything. Instead, the fighter is silently receiving the aftermath of the DM’s charitable gift to the wizard: a fight free of damage, risk, or any real danger.

Of course, if the fighter actually falls unconscious, that’s a great time for the wizard to start panicking! But the fighter again, hasn’t actually done anything to help the wizard or obstruct the monsters. All the fighter did was provide a hard candy shell that the monsters voluntarily chose to bite through before getting to the wizard’s soft, chewy Tootsie-Roll in the middle.

You might as well have put up a wall of stone spell between the wizard and the monsters for all the power or agency the fighter had. (And, of course, many wizards actually do.)

Fighters and barbarians (and, as the Effective Hit Points chart suggests, rogues and monks) are not tanks by their own agency or choice. They’re tanks because the DM arbitrarily decided that the monsters have to hack through their hit points before they can get to the real treat: the casting classes.

Meanwhile, the martials’ damage is doing approximately nothing compared to the profane amounts of damage the casters can milk from area-of-effect spellwork. If the martials are getting anything done at all, it’s because a caster generously decided to cast a transmutation spell like haste or polymorph instead of an evocation spell like lightning bolt. And even then—it’s still the right decision for the monsters to target the casters first—and again, the martials have no way of preventing this from happening!

From Each According To His Role

This all amounts to, approximately, a Big Problem. Let’s recap what we’ve learned:

DPS casters are better at DPS than martials, including DPS martials like rogues or paladins.

Support casters can allow martials to compete with DPS casters, but can almost always choose to spend their actions on DPS spells instead. (Then, because of the Concentration limitation, support casters will then spend the rest of combat casting DPS spells anyway.)

Martials are functionally useless as tanks because they have no mechanism to force monsters to target them instead of casters, outside of the DM’s goodwill. As such, martials’ only role is to serve as “sacks-of-HP” that monsters choose to punch through before going after the casters.

As they say, diagnosing a problem is the first step to solving it. Let’s go through these one-by-one.

First: The DPS Caster problem. At the end of the day, DMs often prefer combats with groups of monsters to combats with solo monsters, which means that area-of-effect spells like lightning bolt will always out-damage RAW martial DPS. We have a few possible ways to address this:

We can push DMs to run longer adventuring days, forcing wizards to expend more spell slots and eventually run out of gas. However, most modern DMs prefer shorter adventuring days to longer ones, and casters who are forced to cast nothing but cantrips will inevitably—you guessed it—ragequit.

We can create battlefields that punish AoE casters, either because there’s a substantial risk of hitting allies or because there’s a substantial risk of destroying the environment. The former is only possible if the monsters intentionally arrange themselves to prevent optimal AoEs, which is a big burden to place on DMs who don’t enjoy tactical combat or who use ranged attackers. The latter similarly forces DMs to create combat spaces that the PCs both can destroy and will necessarily care about destroying—which is both limiting to a DM’s narrative freedom and fairly difficult to come by. (“Dungeons,” as per the name of the game, tend not to be particularly flammable!)

Alternatively, we can nerf DPS spells like lightning bolt and fireball and spirit guardians to be—at best—competitive with martial damage, if not strictly inferior. (This way, casters can act as crowd-control by mowing down low-hit point minions, and allowing the DPS martials to save their damage for bigger bosses.) Unfortunately, these DPS spells are beloved by casters and pretty iconic to D&D as a brand. Nerfing them would cause—yet again—more ragequits.

Alternatively, we can bump up the damage of DPS martials like rogues and paladins to match or grossly exceed the DPS of DPS casters. This seems…genuinely pretty viable!

How might we do that? In the case of rogues, that might be as easy as doubling their Sneak Attack damage. In the case of paladins, that might take the form of increasing their Smite damage, giving them more Smites per day, or giving them some kind of passive spirit guardians aura that they can activate a certain number of times per day.

Second: The Caster Choice problem—i.e., the fact that most casters can simultaneously act as both Support and DPS casters, thereby dominating the outcome of every combat encounter regardless of other class’s contributions. How might we solve this one?

We could change the Concentration rules such that casting a leveled spell immediately forces a Concentrating saving throw with a DC of 10 plus the spell’s level. This would be a pretty staggering change, but one I’d be genuinely curious to see in practice.

We could also segregate DPS spells (the evocation school of magic) from support spells (the transmutation school of magic) to force casters to choose one or the other, but not both. This would be, amusingly enough, a sort-of-return to 3.5 wizardry, but one I’d nonetheless be curious to see in action.

Either of these changes would be highly controversial—but I’m convinced that they’d be a solid move forward compared to the godlike caster status quo we have now.

Third: The Martial Tank problem. This is for sure the most important issue to solve, coming up just ahead of the DPS Caster problem.

Tanks like fighters and barbarians (and paladins, if they’d rather be tanks than DPS) deserve something to do in combat. It doesn’t need to be complex!—it’s important, at least to me, to preserve martials as a beginner-friendly option—but it does need to be substantive.

So what might that look like?

We could give the tanks more DPS than the DPS casters, but less than the DPS martials, thereby encouraging the monsters to deal with them first. But that just causes a runaway DPS spiral, making the PCs into even worse glass cannons than they are now. (Plus, if the martials get buffed by support casters, that’s just even more reason for smart monsters to target the casters first.)

Alternatively, we could give the tanks options that allow them to prevent monster movement and/or attacks. For classes like the fighter and monk, this could be a great flavor win—picture a fighter that comes with a built-in Sentinel feat (“Your fight is with me!”), or a monk whose punches can protect allies from incoming enemy attacks.

Finally, we could give the tanks features that allow them to punish monsters that attack other PCs. The barbarian (whose MO is to plunge straight into battle) and the paladin (who’s the clearest analogue for a “gallant knight” that 5th Edition has) could fit nicely here. Imagine a barbarian who can threaten every creature in-range, or a paladin who can take immediate vengeance on any creature that attempts to attack their ward.

Fortunately, we don’t need to imagine it—because I’ve just developed a prototype version of these features. You can find them here, alongside a proposed reorganization of caster spellcasting to fit Problem Two above. These features haven’t been rigorously playtested yet, but I’m curious to see how they feel in real-life gameplay.

My proposed solutions, of course, aren’t the only possible solutions. If you have any thoughts on how you’d fix these problems—or any critique on whether they even are problems at all!—I’d love to hear them in the comments.

Special thanks to EpicBlunders and TableSalt for feedback and review. Cover image credit to Wizards of the Coast.

DragnaCarta is a veteran DM, the author of the popular “Curse of Strahd: Reloaded” campaign guide, a guest writer for FlutesLoot.com, the developer of Challenge Ratings 2.0, and the former Dungeon Master for the actual play series “Curse of Strahd: Twice Bitten.”

To read more of Dragna’s articles about D&D design theory, DMing tips & tricks, and principles of storytelling, subscribe now to receive new articles in your inbox.

To support Dragna’s work and get DMing resources and mentoring, you can click here to check out his Patreon.

To get Dragna’s hot takes and commentary, you can click here to follow him on Twitter.

Class Effective DPS values were calculated using a class’s most effective damage-dealing spells and/or abilities over the course of a 12-round, 3-encounter adventuring day, assuming a short rest after each encounter.

It’s worth pointing out that the wizard, assuming access to mage armor, isn’t that far behind the paladin, one of our DPS classes! Why? You would think that paladins, due to their high Armor Class values, are natural-born tanks. You would also be wrong. Due to their mutual access to Evasion and respective access to Patient Defense and Uncanny Dodge, monks and rogues can absorb far more incoming damage than paladins can. The same is true for fighters, who can regain boatloads of lost hit points using their Second Wind ability. Even the paladin’s Aura of Protection ability is better at protecting the rest of the party from damage than themselves.

There are a few minor exceptions, which (due to the need to expend resources, force a saving throw, or successfully hit an enemy) tend to prove the rule. A non-exhaustive list includes the Battlemaster Fighter’s goading attack, the Ancestral Barbarian’s ancestral protectors, and the Paladin’s compelled duel.

Really good article!

However, I'm surprised there are little mentions to the warlock, as it is seen by the optimization community as the DPR baseline or "warlock baseline", as presented by Treantmonk here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zg0bAl1WPGQ .

Essentially, you calculate the dpr of a warlock casting hex + eldritch blast (with agonizing blast), applying the chance to hit and assuming the warlock will increase their charisma every ASI (so that they have a constant 60-65% chance to hit a generic enemy of the appropriate CR) and you obtain the baseline damage any character should do. The warlock does this with a no-brain effort, so any build that falls below this baseline without doing anything else of value is suboptimal

Probably should have dropped my comments here instead of spamming your twitter.

In my playtest the easiest way to balance Martial vs Caster discrepancy is

* Shorten short rest to 5mins. (You mentioned this before and my playtest agree with you)

* Give all Fighters and Barbarians access to battle master style maneuvers(been using LaserLlama's alternative class series to test this)

* Make Ranger a prepared caster class and buff their spell list.

* Dump GWM and Sharpshooter. Replace it with a general game feature that you can subtract your proficiency bonus from the attack roll to add double that to the damage roll.

* Bonus feat a level 1 and every four character levels.

Does that fix everything? No. Monk and Rouge are still the odd mans out as they don't use spells and if there is a way to shove maneuvers into their base class I haven't seen it yet. But I think its the right track. Martials need a shared power system like casters have so roles are separated from classes and power can be added organically to martials over time. A shared system also allows players to choose how much complexity they want to deal with, instead of having that choice made for them the instant they pick a class.